Night 1:Pointing with the telescopes

How to get rid of the background

How to get rid of the background

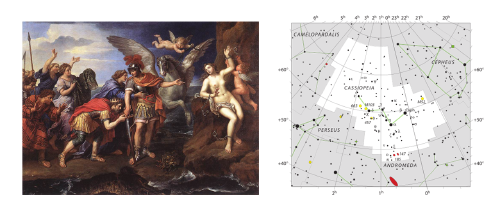

In Greek mythology, Cassiopeia was an arrogant and vain woman who boasted of her incomparable beauty. For astronomers, Cassiopeia is a constellation that can be seen in the Northern hemisphere throughout the entire year.

Mythology or astronomy? Better choose both. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

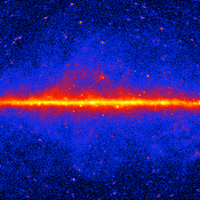

As a gamma-ray hunter, I go in search of Cassiopeia A, a remnant of the supernova (the stuff left over from a stellar explosion), which is the brightest extrasolar radio source in the sky. We affectionately call it CasA (KASEIi,… it’s not Spanish for ‘home’!). And off we go in search of the gamma rays that it emits. And, of course, CasA is in the constellation of Cassiopeia.

I point the MAGIC telescopes at CasA and I wait. It’s going to be a long night.

When we point at a source like CasA, how do we know that what really comes to us came out of CasA? The Universe is full of backlighting, and we must hear that in mind when catching gammas

When a video is recorded in a place where there’s noise, the sound technician has a trick to get rid of it in the final editing. They start recording when everyone is silent and then remove that noise from the video. What they’re doing with this trick is eliminating the background noise.

We do something similar when we want to remove the background light of the universe. We point the telescopes at a place we know that gamma rays don’t come from and then we subtract that from the data that comes from the place in the sky where we think gamma rays do come from.

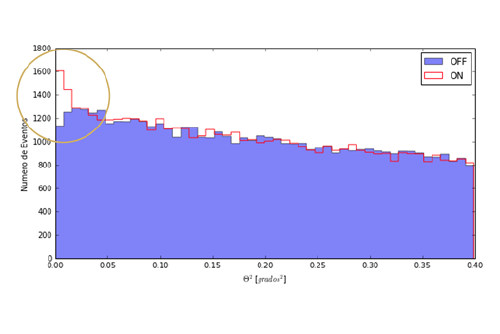

We call the first recording OFF: we know that gamma rays don’t come from there, so all we get is background noise.

We call the second one ON: we think that gamma rays come from there but we’re not sure.

The final trick is to subtract: ON-OFF, which is the signal minus the noise.

Blue for noise, red for the possible signal. Don't forget to get rid of all the light that doesn't come from gamma rays, or you won't really know for sure what you are looking at.

After, observing CasA for 3 hours, I start to analyse the data that I’ve got. And that means that I start using code to select and add events that we know are gamma rays detected by our telescopes. And, of course, subtract the background noise that we detected in a place near CasA.

Again, don’t be put off by the code. It’s not a monster, it’s a tool.

On the right page, you can see how I analyse the first data that comes from CasA and I draw my first thetaplot. That probably sounds reall weird to you, but that’s what we call these graphs.

If you’re brave enough, this may also be your first gamma-ray analysis!

%matplotlib inline

from noche1_4 import *

Our first data

Now we have real gamma ray data.

- In the file casa we have the ON data (remember what that was?)

- In the file off we have the OFF data.

Do you remember how to read the data?

leer("casa"),...

Let’s see what they look like. Remember that the first thing is to understand the data format.

leer("casa")

leer("off")

theta2

------

0.038

0.288

0.275

0.091

0.141

0.324

0.113

0.06

0.088

0.25

...

0.128

0.335

0.316

0.016

0.33

0.125

0.283

0.263

0.012

0.001

0.37

Length = 1556 rows

theta2

------

0.279

0.08

0.011

0.372

0.107

0.148

0.023

0.308

0.396

0.097

...

0.053

0.225

0.055

0.368

0.268

0.068

0.117

0.192

0.37

0.28

0.24

Length = 1523 rows

There’s only one column called theta2.

Did you notice that in these files I only have one value per gamma detected? That’s called the theta square, from the Greek letter. Theta2 indicates the distance between the point in the sky where the particle we have detected came from and the source that I am observing. That’s to say, CasA for the ON data and an empty site for the OFF.

To understand these data, it’s best to represent them. We’ll draw a graph called a histogram, which shows the number of detections in each range of Theta2. Check this out:

Let’s show the CasA and OFF histograms:

histograma("casa")

histograma("off")

To be able to compare, it’s best to make the two histograms at the same time:

histograma("casa", "off")

Sometimes OFF wins and sometimes ON wins. Near 0.00, which is where CasA is, it seems that the ON wins, right? But we cann’t be so sure.

The truth is that with only three hours of observation, we can’t do much more. We need many more hours to be able to catch more gammas and be sure that CasA is a source of gamma rays.

Dictionary of the gamma ray hunter

Active Galactic Nuclei

There's party going on inside!

This type of galaxy (known as AGN) has a compact central core that generates much more radiation than usual. It is believed that this emission is due to the accretion of matter in a supermassive black hole located in the centre. They are the most luminous persistent sources known in the Universe.

Find out more:

Black Hole

We love everything unknown. And a black hole keeps many secrets.

A black hole is a supermassive astronomical object that shows huge gravitational effects so that nothing (neither particles nor electromagnetic radiation) can overcome its event horizon. That is, nothing can escape from within.

Blazar

No, it's not a 'blazer', we aren't going shopping

A blazar is a particular type of active galactic nucleus, characterised by the fact that its jet points directly towards the Earth. In other words, it’s a very compact energy source associated with a black hole in the centre of a galaxy that’s pointing at us.

Cherenkov Radiation

It may sound like the name of a ames Bond villain, but this phenomenon is actually our maximum object of study

Cherenkov radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted when a charged particle passes through a dielectric medium at a speed greater than the phase velocity of light in that medium. When a very energetic gamma photon or cosmic ray interacts with the Earth’s atmosphere, a high-speed cascade of particles is produced. The Cherenkov radiation of these charged particles is used to determine the origin and intensity of cosmic or gamma rays.

Find out more:

Cherenkov Telescopes

Our favourite toys!

Cherenkov telescopes are high-energy gamma photon detectors located on the Earth’s surface. They have a mirror to gather light and focus it towards the camera. They detect light produced by the Cherenkov effect from blue to ultraviolet on the electromagnetic spectrum. The images taken by the camera allow us to identify if the particular particle in the atmosphere is a gamma ray and at the same time determine its direction and energy. The MAGIC telescopes at Roque de Los Muchachos (La Palma) are an example.

Find out more:

Cosmic Rays

You need to know how to distinguish between rays, particles and sparks!

Cosmic rays are examples of high-energy radiation composed mainly of highly energetic protons and atomic nuclei. They travel almost at the speed of light and when they hit the Earth’s atmosphere, they produce cascades of particles. These particles generate Cherenkov radiation and some can even reach the surface of the Earth. However, when cosmic rays reach the Earth, it is impossible to know their origin, because their trajectory has changed. This is due to the fact that they have travelled through magnetic fields which force them to change their initial direction.

Find out more:

Dark Matter

What can it be?

How can we define something that is unknown? We know of its existence because we detect it indirectly thanks to the gravitational effects it causes in visible matter, but we can’t study it directly. This is because it doesn’t interact with the electromagnetic force so we don’t know what it is composed of. Here, we are talking about something that represents 25% of everything known! So, it’s better not to discount it, but rather try to shed light on what it is …

Find out more:

Duality Particle Wave

But, what is it?

A duality particle wave is a quantum phenomenon in which particles take on the characteristics of a wave, and vice versa, on certain occasions. Things that we would expect to always act like a wave (for example, light) sometimes behave like a particle. This concept was introduced by Louis-Victor de Broglie and has been experimentally demonstrated.

Find out more:

Event

These really are the events of the year

When we talk about events in this field, we refer to each of the detections we make via telescopes. For each of them, we have information such as the position in the sky, the intensity, and so on. This information allows us to classify them. We are interested in having many events so that we can carry out statistical analysis a posteriori and draw conclusions.

Gamma Ray

Yes, we can!

Gamma rays are extreme-frequency electromagnetic ionizing radiation (above 10 exahertz). They are the most energetic range on the electromagnetic spectrum. The direction from which they reach the Earth indicates where they originate from.

Find out more:

Lorentz Covariance

The privileges of certain equations.

Certain physical equations have this property, by which they don’t change shape when certain coordinates changes are given. The special theory of relativity requires that the laws of physics take the same form in any inertial reference system. That is, if we have two observers whose coordinates can be related by a Lorentz transformation, any equation with covariant magnitudes will be written the same in both cases.

Find out more:

Microquasar

Below you will learn what a quasar is...well a microquasar is the same, but smaller!

A microquasar is a binary star system that produces high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Its characteristics are similar to those of quasars, but on a smaller scale. Microquasars produce strong and variable radio emissions often in the form of jets and have an accretion disk surrounding a compact object (e.g. a black hole or neutron star) that’s very bright in the range of X-rays.

Find out more:

Nebula

What shape do the clouds have?

Nebulae are regions of the interstellar medium composed basically of gases and some chemical elements in the form of cosmic dust. Many stars are born within them due to condensation and accumulation of matter. Sometimes, it’s just the remains of extinct stars.

Find out more:

Particle Shower

The Niagara Falls of particles!

A particle shower results from the interaction between high-energy particles and a dense medium, for example, the Earth’s atmosphere. In turn, each of these secondary particles produced creates a cascade of its own, so that they end up producing a large number of low-energy particles.

Pulsar

Now you see me, now you don't

The word ‘pulsar’ comes from the shortening of pulsating star and it is precisely this, a star from which we get a discontinuous signal. More formally speaking, it’s a neutron star that emits electromagnetic radiation while it’s spinning. The emissions are due to the strong magnetic field they have and the pulse is related to the rotation period of the object and the orientation relative to the Earth. One of the best known and studied is the pulsar of the Crab Nebula, which, by the way, is very beautiful.

Find out more:

Quantum Gravity

A union of 'grave' importance ...

This field of physics aims to unite the quantum field theory, which applies the principles of quantum mechanics to classical systems of continuous fields, and general relativity. We want to define a unified mathematical basis with which all the forces of nature can be described, the Unified Field Theory.

Find out more:

Quasar

A 'quasi' star

Quasars are the furthest and most energetic members of a class of objects called active core galaxies. The name, quasar, comes from ‘quasi-stellar’ or ‘almost stars’. This is because, when they were discovered, using optical instruments, it was very difficult to distinguish them from the stars. However, their emission spectrum was clearly unique. They have usually been formed by the collision of galaxies whose central black holes have merged to form a supermassive black hole or a binary system of black holes.

Find out more:

Supernova Remnant

A candy floss in the cosmos

When a star explodes (supernova) a nebula structure is created around it, formed by the material ejected from the explosion along with interstellar material.

Find out more:

Theory of relativity

In this life, everything is relative...or not!

Albert Einstein was the genius who, with his theories of special and general realtivity, took Newtonian mechanics and made it compatible with electromagnetism. The first theory is applicable to the movement of bodies in the absence of gravitational forces and in the second theory, Newtonian gravity is replaced with more complex formulas. However, for weak fields and small velocities it coincides numerically with classical theory.

Find out more: